Helga Jakobson | Casey Koyczan | Erika Jean Lincoln | Sylvia Matas | Taylor McArthur

Events

Opening Reception: Thursday September 21, 7 PM

Lunch & Look Artist Tour: Friday September 22, 1 PM

Talks and Workshops:

“Interfacing with Nature” with Helga Jakobson – Saturday, October 7th, 1 PM CT. On site.

What does a plant sound like? Do they think and feel? Can they see? Take a nature walk with transdisciplinary new media artist Helga Jakobson and explore the Assiniboine Food Forest through the lens of speculative fabulation. Throughout the workshop, participants will use digital and analog art making techniques and media to interface with the natural elements that we encounter.

Artist talk with Sylvia Matas – Saturday, October 28th, 1 PM CT. Online.

Sylvia will be speaking about her recent video work including her video House Plant which is part of the exhibition Oneirophyte at the AGSM. She will be talking about her process, research, and source imagery that led to the creation of these video works.

Watch it live.

Artist talk with Casey Koyczan – Saturday, November 4, 2023, 1 PM CT. Online.

Casey will speak about his journey toward the creation of įdii : past in time, referencing animation generally and the multiple techniques he puts to use.

Watch it live.

Digital Twinning with Derek Ford: Introduction to 3D Scanning and Printing – Saturday, October 21st and Sunday, October 22, 1-4 PM. Assiniboine Community College, 1430 Victoria Avenue East.

In dreams, action and movement are not confined by the rules of naming and physics that we must abide in waking life–we can see around corners, decide whether our suspicions and predictions will be correct or surprise us, and understand one thing to be many things. We can do all of this without reflection, without words. The difficulty of understanding the complex lives of plants might not be a difficulty at all if we could hold on to that oneiric state of mind. It is imagination, rather than intelligence, that confounds the division between one sort of life and another, because it is the kind of thinking that responds to itself, rather than to external, physical situations. This is thinking that wonders, anticipates, misremembers, interprets, opines, and cannot be rendered artificially.

Plants are so mundanely and obviously alive and intelligent that academic, artistic, and scientific attempts to prove so shout into the wind. One such experiment, conducted by a German lab in 1987, linked the electric impulses given off by plants to a dictionary containing 900 common words. Since so many combinations of words can form meaning, the scientists were skeptical that what they had invented was a randomness generator, until following a few adjustments to the syntactical algorithm, a magnolia tree expressed the following sentiment:

Plants before all others.

Someone achieves peace in dreams,

without taming–beyond human beings.

The “before,” “beyond,” and “someone” of this phrasing is ambiguous to the point of being menacing. The security of classification systems is noticeably absent—perhaps with proper nouns the magnolia could be more literal.

The artists in Oneirophyte take care to literalize their plants, and they do this by stepping back to an arm’s length and wedging an interface between themselves and their subjects. The artist is thus rendered algorithmic while the plant may add nuance to its self-expression, considering context and media as it does so. There is no question here as to whether human perception is sufficient. Not only is it insufficient, but detrimental, drowning out other ways of knowing with its hubris. The works of art are cyborgs with an artist on one end and a confounding intelligence on the other, separated by an artless mediator.

There is something of play in all the artwork in Oneirophyte due to its interactivity, the implication of the human visitor in the plant realm. In all the masses of research that have been done on plant sentience and communication, writers frequently introduce their studies with a defensive tone, and it is often directed towards the Western scholarly and scientific communities, who overwhelmingly agree that without a central cognitive system, plant intelligence is not possible. Any resemblance would be mere wordplay.

But of course, all language plays with words, and the generative power of art is that it can move at the speed of play, as opposed to Western science, which moves at the speed of evidence. These artists are using digital media to think about plants for the same reason that AI technologies are being rolled out for use in creative fields: seeing what will happen is an end in itself. The tinkering, strolling, and eavesdropping of these practices creates a space that is open to more wondering. Playing with these words, “wondering,” “imagining,” “dreaming,” in proximity to plants widens the scope of all of them, makes them less material, more translucent, more alike, more singular.

There is a joke among cyberneticists about defining the discipline because it encompasses seemingly everything that has a determined structure, from laws of entropy to the events of the central nervous system, from natural selection to self-replicating machines. Today, the word “cybernetics,” which shares its Greek root with “government,” provides the prefix to all things computer: cyberpunk, cyborg, cyber security. Prefixes are sub-categoriesthat reflect a desire to get more specific. The contrary desire accounts for the work in Oneirophyte. Telling a biological story technologically creates a feedback loop–a categorization down to the electron–so massive that it might as well be everything.

Adapted from the exhibition text by Lucie Lederhendler

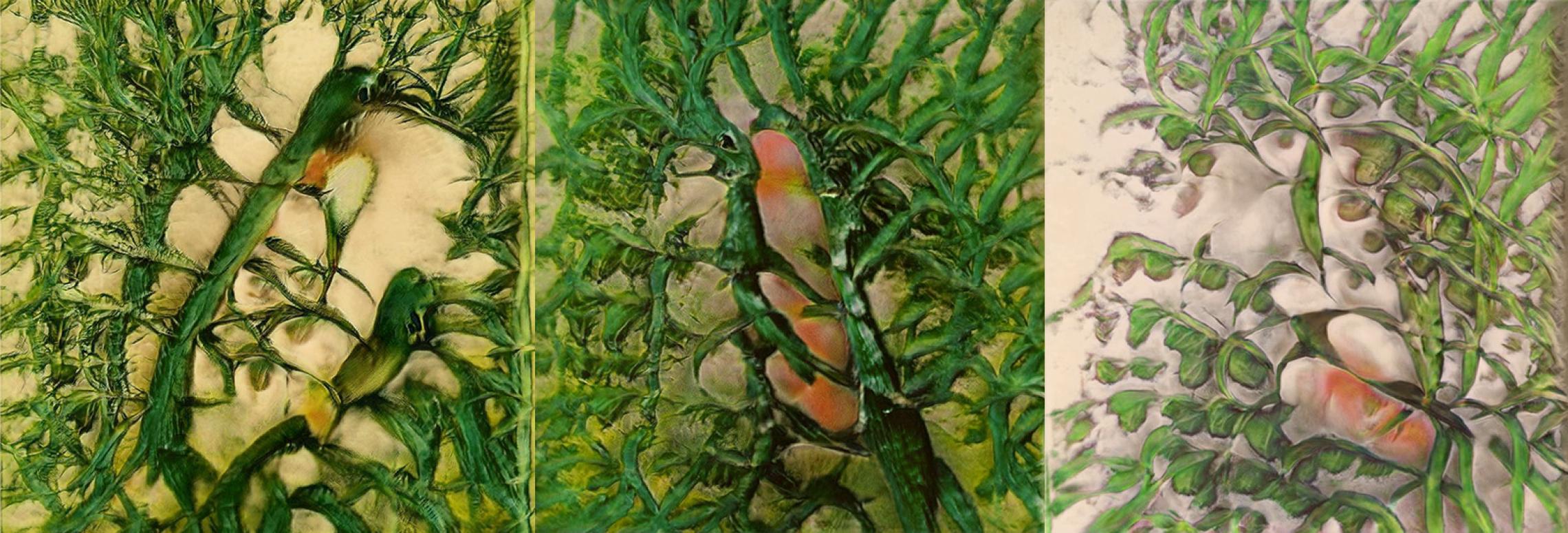

Stills from Erika Jean Lincoln, Arboreal Intuitions. 2023.