AGSM Curator Lucie Lederhendler in conversation with Artist Craig Milliken. February 2022.

LL: In the texts [from your past four exhibitions at the AGSM] a lot of them were really formal. I think that’s because you are pretty formalist as an artist, but because this is more of a retrospective, could you tell me about your life first? Where did you grow up?

CM: Well, I grew up on a farm, in Southwestern Manitoba. Three miles from the town of Reston, I used to tell people. That’s in the Southwest.

LL: What kind of farm was it?

CM: Mixed farming. My dad had some cattle and grain. We were right on the Pipestone Creek, which flows into Oak Lake.

LL: That creek was right on the farm?

CM: Yeah, and there was an oxbow. Which I–

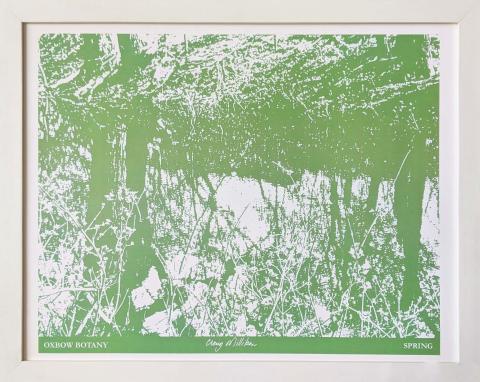

LL: Which you’ve documented.

CM: Yeah. Before all the elms–the intent was to do it before all of the elms disappeared. Died from Dutch Elm disease? They’re all dead now.

LL: Has anything taken the place of the elms?

CM: There are other trees there. But particularly close to our house, there were a lot of big old elms. One hundred years or more.

LL: It must have really changed the feeling of your house, when they were gone.

CM: Yeah, but I grew up and went to university, and I got a bachelor of environmental studies, and a degree in landscape architecture.

LL: What attracted you to landscape architecture?

CM: Well growing up, my parents were quite large into gardening and landscaping. I came across a pamphlet in high school for architecture, that said if you’re good at math and you’re artistic you would be suitable for architecture. Then I found out about landscape architecture.

LL: So it’s combining the art and the nature that you liked in the farm, and also math, that you enjoyed?

CM: Yeah. It was two years before I could take the landscape architecture program. It was a new program, and they didn’t have approval. I was the only one that wanted to go into landscape architecture. I spent that time working at different jobs. One summer for a firm of landscape architects, and for about a year and a bit I worked for campus planning at the university. Just doing drafting. In between degrees I went to Europe, mainly England. When I came back I went into landscape architecture.

LL: And did you enjoy it? The drawing was probably fun for you.

CM: Well, uh, I did really well in landscape architecture. It had an aspect of city planning to it too. Still didn’t graduate until 1975, but I started university in 1965. We started out with seven people in our class and I was the first one to graduate. I took some time off and then I finished my thesis.

LL: So then as a landscape architect, you were working with urban landscapes? Designing?

CM: Somewhat. I worked a lot of different places–it’s an up-and-down profession, like architecture.

LL: In what way? Just sometimes you have work and sometimes you don’t?

CM: Yeah, well they lay you off. Some places I wasn’t fast enough. [The work culture is] kind of a–have this done in a day, have this done in two days. It’s a fairly stressful profession, because you’re paid to be creative and you know, good. I was good at designing, graphics, but working drawings I was challenged with.

LL: Yeah. It’s being creative on a deadline.

CM: Yeah.

LL: Is there any landscape that still survives that you designed from that time?

CM: The west entrance to Assiniboine park is quite similar to the original. And I worked on the study that recommended developing the Forks. I played a small part, but I still was a part of that.

LL: OK. And how long were you a landscape designer? An urban designer?

CM: Well, sort of–1969 and I did drafting for a firm of landscape architects. Then off and on I worked as a landscape architect up ‘til 1990. As my career kind of waned, for mental health reasons, I focused more and more on the visual arts. I started pursuing that in 1980.

LL: Ok, so there was some crossover.

CM: I was in a commercial gallery in Winnipeg, then the Mel Mechenko Gallery. He got fed up with the arts scene and Winnipeg and moved to Vancouver. This is back in 1983 and I got into some art galleries in Winnipeg. Like most of them, they fold sooner or later, usually sooner [laughs] And I travelled around quite a bit–when one job ended I’d find another one in another city. So I lived all over Western Canada, and Toronto.

LL: Is that a fun time of your life to remember? Is there freedom there or less security?

CM: Yeah for sure. I had stressors, though, starting over again, but I had connections in each of the cities, people I had known at university.

LL: That’s important.

CM: Yeah. I haven’t worked as a landscape architect since 1990. But during that time I was sort of pursuing an art career.

LL: I think you can really see how that really really meticulous technical drawing influences your art. Pretty much everywhere.

CM: Right. The arcs and bars. I started doing the drawings because the sculpture did quite well, but there were storage problems. So I switched.

LL: I was going to ask you to put the work in [chronological] order. I don’t know if you work simultaneously or fixate [on one series]?

CM: Well I did a little bit, yeah. Most of all when I was unemployed, I’d fill my time. I first started out doing just straightforward pastel landscapes referring to photographs.

LL: Oh, I’ve never seen those.

CM: Then I was in Saskatoon and my psychiatrist suggested that I take a course at the university. So I did that. The one I chose was a sculpture course. I did quite well with that, but most of that work was left behind or destroyed.

LL: Because of storage again?

CM: Yeah. And then after sculpture–which continued for a while–I started doing my pencil landscapes which I can’t do anymore. I don’t have the hand and eye and hand control. Then I got my waterworks from just my own idea. Well you’re familiar with mylar, which is a drafting material? I used it as a canvas and a pond at the same time. I would mist the mylar with a spray bottle then I would paint on the colour, or a metallic. I’d drip paint and mist it some more, and then I–it would kind of flow around and like sediments. In a stream.

LL: You showed those at the AGSM in ‘97.

CM: Yes.

LL: You say they were metallics?

CM: Just one metallic. The initial paint was metallic, and I would drip another one or two or three colours.

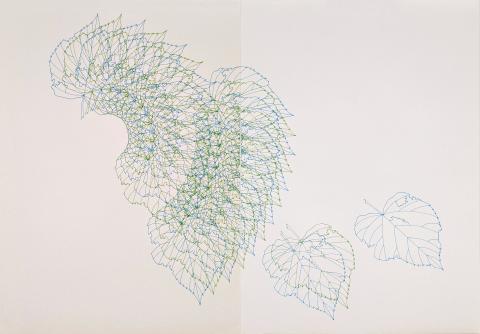

LL: I see. You use some metallics in the leaf mandalas as well.

CM: Yes, some of them.

LL: Okay, so you were drawing and you did some of those graphite landscapes after the pastels, and then you went to sculpture, and then waterworks.

CM: It would be about 1986 that I started doing sculpture.

LL: And we had that exhibition in ‘92, at the AGSM.

CM: Yeah. I did pretty well with the sculpture, and the leaf mandalas sold as well.

LL: Yeah, but those came later, right?

CM: Yeah. [I got that idea when] I was drawing cards. I thought of taking leaves and tracing them in different colours and metallics and non-metallics and–just folding the paper in half to create a card. Then I realized if I put four of these eight and a half by eleven sheets together, I had a mandala. It sort of grew in size from there. I had a show of those, Jennifer Woodbury was the curator/ director then.

LL: So that was, jumping, that jumped forward a lot and we haven’t talked about your photography. So where’s the photography?

CM: Right I started doing that seriously when– well I was back in Reston, I was unemployed, and I just wanted to document them before they all died.

LL: So [the photography] started with the Oxbow Botany.

CM: Yeah. I should have called it Vanishing Elms but [laughs].

LL: We can call it that now!

CM: My brother told me that they’re growing back. But they’ll only grow to be such an age, and then the disease and the fungus will get back in them.

LL: Oh, is that right? It infects the land? You can never grow elms there again?

CM: No, no. The elms will grow again. But they’ll grow to a certain size, fairly small, and then they become vulnerable again to the beetle and the fungus.

LL: Yep. You know there’s so much work, I kind of couldn’t choose a [single] series–that’s why I’m so interested in putting them all in a chronology.

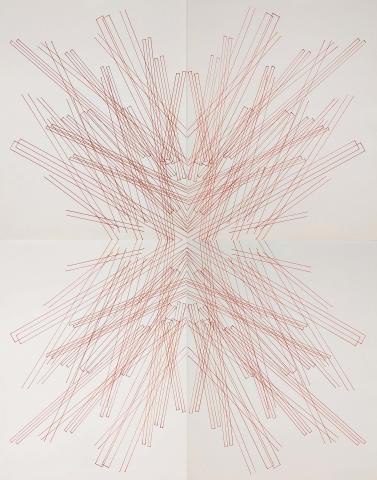

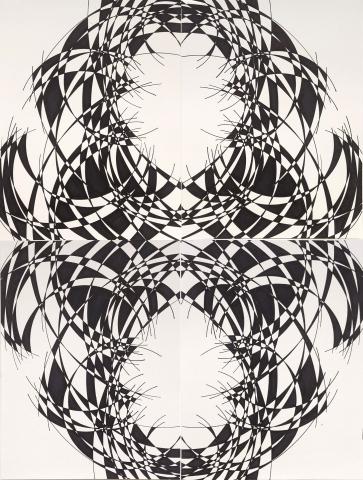

CM: Time, yes, oh for sure. I actually–I started doing the geometrics ‘cause I wanted to continue using the arcs and bars in a sense, from my sculpture.

LL: Yeah.

CM: I’ve been pleased with the way they’ve turned out.

LL: Yeah, there’s definitely a through line from the sculpture to the geometrics. So where do those fit in? Those are more recent, you would say?

CM: Yeah, they’re the most recent work. I had a show of [them in 2016]. I’ve had four shows at the art gallery.

First one was the sculpture. Then the waterworks. And then the leaf mandalas, and then the geometric drawings. They were just line drawings, I didn’t have any of the interstices coloured in, but then I started to colour them in. And I think–well, I think they’re as good as my sculpture work. But you would be a better judge of that.

LL: [Laughs] We have to talk about your process, especially when it comes to the mandalas and the geometrics.

CM: Right, I use a light table. The leaf mandalas, I drew a template on mylar, sort of like a pie with different wedges. And then I had drawings, line drawings of different leaves. So I would position them, and then reposition them, to go around in a circle, and hence, make a mandala.

LL: And so the-the original template, is that from a leaf, that outline?

CM: Yes.

LL: 100% to scale?

CM: Pretty much, yeah.

LL: And how do you choose your leaves?

CM: Just native leaves.

LL: Yeah? You just go on a walk and pick one? Or– because there’s one of your poplar templates, that’s quite eaten up. It’s got holes in it and tears and things. Which is noteworthy because it’s such, you know, precision artwork.

CM: Yeah I guess go.

LL: So they–they’re leaves that you picked up just from the outside and traced when you came inside? And then–

CM: I would photocopy them on a photocopier.

LL: Oh that makes sense, yeah.

CM: It was after that that I got into the geometric drawings.

LL: Yeah. Which are done with a light table as well?

CM: Yeah, like I do–one quarter of the page, I draw, um, and then I flip it over so it’s a mirror image, and it’s also a mirror image up and down. The four panels make the complete work.

LL: When you’re drawing the first panel, is that just instinct?

CM: Is that just intuition? Yes.

LL: How do you know when something’s going to work? Do you keep working it?

CM: Well [laughing] they always look better once they’re in fours. I find. It may not quite be right in composition, but once you double it? That’s my perception.

LL: Yeah, and you have a couple that aren’t the fours, but like three that go horizontally, one after the other. The same with your leaf mandalas, sometimes you have a leaf just floating on its own.

CM: I don’t know why I did that.

LL: I think it’s really interesting because some is so symmetrical, but then others, you’ve intentionally changed the weight from one side to the other, right? So that’s where this precision comes from in the drawings. In the photographs, there are black and white photographs, which I assume are standard processes, correct me if I’m wrong, and then you have very high contrast ones, and coloured ones as well. How do you colourize them?

CM: I just went to a commercial artist. He had his own business here in Brandon. He had very good digital printer, that he rented, and I had him simply apply a different colour for each season.

LL: And the really high contrast?

CM: I saw some work done like that, I thought, oh this is great [laughs]. So that’s why I decided it would be suitable. My photography now–it’s a little bit high contrast.

LL: But I assume this isn’t digital photography.

CM: Oxbow Botany wasn't digital, it was a single lens reflex camera. Combined with a poor quality printer. Which, using them together created the high contrast. But I have a digital camera now. I don’t get much opportunity to go out [laughing]. I haven’t done any photography in two years ‘cause of–mainly because of covid.

LL: Sure. But what you’re really interested in is that nature, right?

CM: Yeah. It’s the details I like to photograph.

LL: I think the reason that I took the photography is because I think that everybody will notice that what you’re attracted to in a landscape is lines that look like those lines from the abstract pieces, right? Where you zoom in on the shape of a branch, it’s about the shape of the whole tree, but about the way that it cuts your frame, right? Does that make sense to you?

CM: Ha! No. Sorry, Lucie.

LL: [Laughing] I like that your relationship with nature started out with something kind of methodical, with landscape architecture?

CM: Oh, okay.

LL: And then, because of the way that you looked at things, the way that you organized things, as your art practice evolved, you kept on doing that, organizing the picture plane.

CM: Okay. You work with line a lot in landscape architecture when you do your different renderings and plans and locations. Although everyone does computer drafting now.

LL: So within these series, if you look at, say, the leaf mandalas, they’re all kind of in a circle, but they’re not identical circles, sometimes they’re spirals, more than circles. Is there a way that you choose the overall composition? Or does it kind of emerge as you’re going through this really slow process?

CM: Yeah, it did kind of emerge. I did the simple mandala, the smaller ones with that I started using eight and a half by eleven sheets–those were just straightforward circles, and I thought I would just kind of terminate the drawing and then start it again on a second page, and finally into a third page. I drew a lot like that, but I don’t know why. I just thought, I like cropping. I like pictures that are cropped

LL: So it’s kind of a combination of spontaneous creation and real structure?

CM: I guess, yeah.

LL: Because you obviously need to plan a lot, you need to choose your colours, you need to choose your leaf. All those. But then you allow it to emerge. Now I want to talk about how much work you have, because it seems like this would all take quite a long time [to make].

CM: Well the mandalas were–well I suppose they take longer than someone might take doing a painting with brushes. That was in contradiction to my pencil drawings, which took quite a bit of work, quite a bit of time. And the geometric mandalas take about a week and a half. I can do the design–I think of them as designs in a sense–the ones that are coloured in take about a day a panel. So four days or more, depends on how much time I spend. I never actually noted, but I would say a week, to a week and a half, to even two weeks.

LL: For the large ones?

CM: Yeah.

LL: What’s your mental state doing this? I’m assuming there’s kind of a trance or a zone element to it? This repetition, when you’re spending these hours and hours making these repetitive lines, is there a mental state that you enjoy about this kind of art-making?

CM: Well, I compare it to knitting or crochet. You know, tracing and filling them in.

LL: In what way?

CM: Well it’s just a fairly simple task that creates the whole. Even to create the drawings themselves, because I do them on tracing paper and then use a light table to trace them on to good quality paper. It gets a little boring [laughs].

LL: It gets boring?

CM: Well the first one and the second one aren’t. But the third and the fourth can be.

LL: I was assuming that there was something kind of meditative about it, either focusing on something simple, or letting your mind just go blank while you do it.

CM: No, it doesn’t go blank [laughs].

LL: So why do you plan for things that you’re going to find boring by the last half of the process?

CM: Well, the total image is worth–it’s more than the sum of the parts.

LL: So you have to finish it, you can’t do it in two. And then what’s your process for, say choosing the colours? Is that something experimental?

CM: Basically, well there’s only so many felt pens available. Actually black works best for the coloured in–it gives the most even [coverage]. And there’s something kind of classic about a black and white. There is to me.

LL: There’s some wonderful textures in the greens and reds too, though.

CM: I kind of modelled them a little bit because it’s hard to get, if you do use the other colours, so that it’s kind of an even surface. Whereas the black, it’s applied the most evenly, easily produced. And there’s something classic about black and white that appeals to me, since I did my photography in it.

LL: Right.

CM: And it’s a little easier to get black and white felt pens. So I suppose that.

LL: That is pretty simple. What are you working on now?

CM: I’m still doing the geometric, mandalas. I have my–it’s a small room but I have a work table in there, and it’s large enough. People keep telling me to do something different, but–

LL: [laughing] who’s telling you that?

CM: Who?

LL: Yeah!

CM: I forget.

LL: [laughs] No I think it’s fine to keep going, because there is something just really, really experimental about it, where you just, you sit down, and you start a new one.

CM: Yeah. There are some things that I have in mind that uh, I would like to start doing some water colours.

LL: Oh yeah. That’s a good one for small spaces too. So, do you have this much work because you’re just always working on something? Or is it because you’ve been doing it for so long?

CM: Partly, yes. Also I have the time, so I’m able to do a body of work.

LL: So there’s never not something on your work table there? There’s always something that you’re working on?

CM: Pretty much, yeah